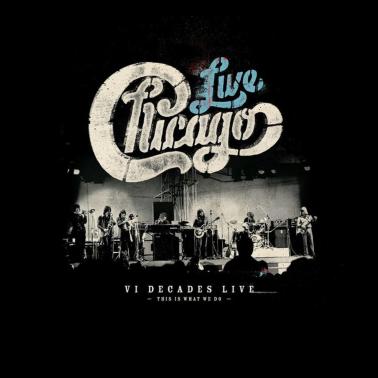

Tim Jessup brings over four decades of experience in recording, mixing, and sound design in music production, film, and television to his work with Chicago. His latest project is a complete restoration and original mix of their two-disc set at Isle of Wight, originally recorded in 1970 and mixed by Jessup in 2017. This live set is the earliest commercially-available live recording of the band, released by Rhino Records as part of their VI Decades Live boxed set, a full review forthcoming on this site.

Stephanie: Many in the recording community and Chicago fans are familiar with your work with the band as the sound designer of the film, Now More Than Ever: The History of Chicago and your innovation in building their first mobile recording studio known as “The Rig” used for their 2014 album, Now (XXXVI). How did you start working with Chicago?

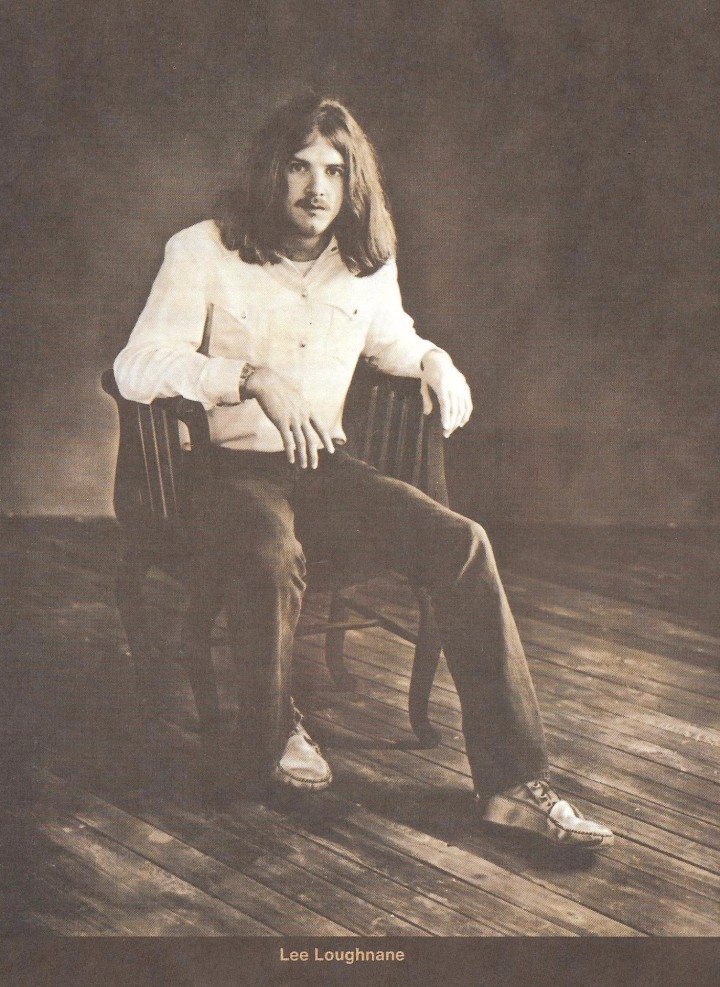

Tim: Lee Loughnane (trumpet) had moved his family to our little town of Sedona, Arizona, in 2010. At the time, Chicago was finishing a concert DVD/Blu-Ray titled Chicago in Chicago, featuring the Doobie Brothers. Management wanted Lee to fly to LA to oversee the 5.1 mix for the concert film. As recent personnel changes in the band have demonstrated, it’s very hard on a family when the bread winner is on the road nine to ten months out of every year. Lee was home between tours and asked management to find someone here in Sedona who could provide 5.1 mixing services so he would not have to be away from his family. Long story short, they asked me to mix the project, but I would have only five days to mix the entire 26 song set before delivery. I told Lee that it was likely not possible to properly mix 26 songs in only five days and that they would probably be wasting their money to try. Lee was willing to roll the dice and asked me if I’d be willing to give it my best try. I literally did not sleep for five days, editing and mixing continuously right up to the manufacturing deadline. It was a Herculean feat, but we made it. No one died, and everyone was relieved and happy with the results. It reminded me of my early days as a staff engineer at Kendun Recorders in Burbank when I would not leave the studio for three days at a time. It develops an obsessive work ethic that you never forsake.

Stephanie: I also understand that you were able to personally witness a Chicago show at Saratoga Performing Arts Center in 1971. How did that experience shape your life as a young musician and your understanding of their musical direction?

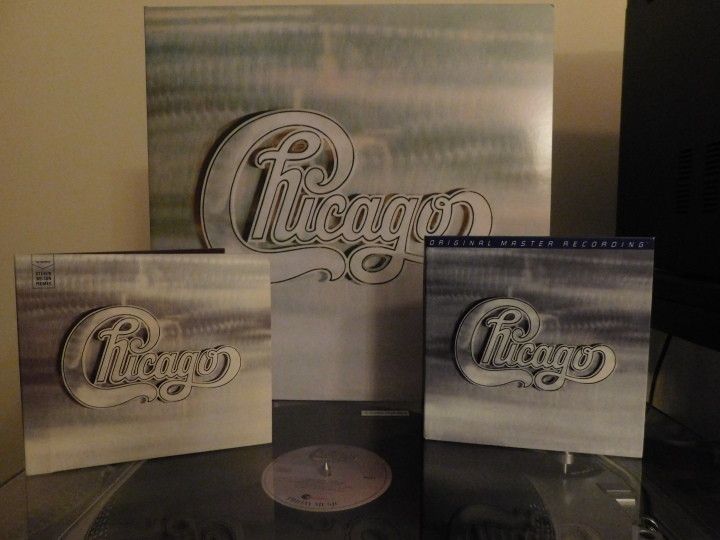

Tim: I was a mere 14 year old pup in 1971. Chicago was actually the first real rock concert I had ever experienced, though I had been playing guitar in local garage bands since the age of 11. You never forget your first rock concert, especially with the huge sound of Chicago. Terry Kath’s fiery, mind-boggling solos, Peter Cetera’s stratospheric vocals, Robert Lamm’s smokin’ B3 playing, Danny Seraphine’s off-the-hook drumming, and that slamming horn section, it was inspirational in every way possible! I had already been sent well down the path of spending my life in music when I saw The Beatles on Ed Sullivan in February of 1964, eating and breathing nothing but the Fab Four throughout the next 6 years, but hearing Chicago live in ‘71 showed me that there was a lot more to it. Their complex arrangements and masterful performances made it plain that I had a lot to learn and much to master. I used to spend many hours listening to and analyzing CTA (Chicago Transit Authority) and Chicago II on headphones. Those mixes became such a part of my DNA that 47 years later I never need to reference them to mix live Chicago recordings.

Stephanie: Fast forward to the fall of last year, Lee Loughnane approached you with a new project, mixing their show from the Isle of Wight, a festival that is often called “Britain’s Woodstock.” Rolling Stone reported at the time that “the piercing brass of Chicago started the campfires on Devastation Hill,” a reference to a colorful campsite just outside the official festival grounds. What was your initial impression about mixing such a historic piece of music history?

Tim: My initial impression was that the Isle of Wight project would likely never be mixed again, and that I would have but only one chance to get it right for all time! The band had considered mixing and releasing the show nearly 20 years ago and chose not to, because of the poor quality of the recording. So why now, what had changed? In a word, everything.

Very powerful and effective restoration tools have evolved recently, such as iZotope’s RX software, that can accomplish what was simply impossible 20 years ago. Even with such powerful tools and mega computer automation, I knew that Isle of Wight would present serious challenges and require innovative techniques to draw out a mix that both the band and the fans would care to lavish in. From the outset, I believed it could be accomplished, but I also knew it would be rife with unknown challenges, demanding solutions that I had yet to envision. Those who have collected bootleg recordings of the IOW show know to what I am referring. In hindsight, there is no way I could have predicted some of the challenges encountered or what it would take to solve them. I re-mixed the entire show five times to bring it to its ultimate fruition, using eight different pairs of monitors, wrestling to get the mix to translate properly on a wide array of home speakers. The final mix was created after (mastering engineer) Dave Donnelly took his first mastering pass at it. We were obsessive about getting it right.

Stephanie: Many have wondered why more archival live shows from Chicago and other legacy artists are still “in the vaults” so to speak. The Allman Brothers and Neil Young are two contemporaries to Chicago who have different models of successfully opening their archives. It’s a chicken and egg question but what came first, the technology (hardware and software) to restore flawed archival recordings or the demands of the market and fans to release them?

Tim: There have long been rumors circulating that there is a “vault” filled with unreleased Chicago recordings. In my experience and conversations with the guys, this is simply not the case. When Rhino Records bought the Chicago catalog, they went through everything that existed on tape, organizing and identifying everything. The simple fact is, Chicago was way too busy touring all of those years to be very conscious about documenting everything on tape. When Peter Pardini was producing the documentary film, he had a very hard time finding anything that existed on old films or video. Thank God, Jimmy (Pankow) had kept some old 8mm film from the early days, but there just isn’t that much material to be found. It was a regret of various band members that there wasn’t more archival material to use in the film. This is why the new Rhino release of Chicago: VI Decades Live is so important. These are truly rare recordings.

But to complete my answer, archival material has a tendency to be embarrassing to recording artists, whether it is due to a poor recording, the performance, or both. So the factors dictating whether an artist is willing to release certain material publicly are going to be determined on an individual basis. An artist like Neil Young made it a priority to record and document most everything he did, and he has few qualms about releasing any of it. Other artists tend to be more judgmental about their historical body of work. The good news is that the technology does finally exist to resurrect archival recordings that were once considered “not commercially viable.” Chicago’s Isle of Wight mix is a perfect example of this. The technology itself has migrated over from the film industry, and has been used for many years to clean up bad audio and noisy dialogue. Music mixers are really just starting to catch on to the miracles of iZotope’s RX software. But software such as this will now make it possible to bring forth many more archival recordings that were once considered “unreleasable.”

Stephanie: The young crew from Pye Records and their mobile recording studio are credited with recording the festival, overseen by the CBS team of engineer Stanley Tonkel and producer Teo Macero. Since CBS didn’t initially release this recording in the early 1970s, you’ve essentially picked up on work started 48 years ago. What was the condition of the source tape that came from the archives of Warner Music Group?

Tim: The show came to us on four reels of one-inch 8-track tape. Physically, they were in great shape. Normally, tapes that are newer than 1972 have a back coating that becomes brittle and sheds badly over time. These tapes must be baked to re-adhere the back coating before they can be safely played. The Isle of Wight tapes from 1970 had no back coating and played beautifully. Magnetic print-through, an echo imparted from adjacent layers of tape after long-term storage, was also not an issue. From the tape box labels, it appeared they had been copied at Back Pocket Recording Studios in New York, not long after the show. There was no way of knowing whether they had been transferred with the European CCIR (Consultative Committee on International Radio) Equalization curve, or the American NAB (National Association of Broadcasters) EQ curve. We had to play the tapes with each calibration curve to choose which one translated best. The CCIR curve has more of a high frequency roll-off, like a pseudo Dolby effect, so the tape hiss was quieter, and the tracks sounded warmer, punchier and fatter with the European curve, especially Danny’s drums and Terry’s guitar. Even if the NAB curve was correct, we preferred the sound of the CCIR curve and that is what we used.

Stephanie: I was pleasantly surprised that Chicago’s full set survived on tape. Initially, what were the most difficult challenges you knew had to be addressed back at your Sedona studio?

Tim: We discovered during the tape transfer that a few songs were missing entire sections. Apparently, the Pye Studio engineers had only one multi-track tape recorder on their remote truck, with no back-up machine running to catch entire songs when the tape ran out during the show. They were changing reels of tape when the band began to play Beginnings and lost the entire intro. and part of the first verse. Similarly, the tape ran out right in the middle of Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?, losing a full chorus and part of the following verse. It was fortunate that these were discovered at the time of the transfer because we also had the 2” 16 track reels from the 1971 Kennedy Center performance. As a back-up, we also transferred the missing parts of the Isle of Wight recording from the Kennedy Center show.

Back in Sedona, I created matching “grafts” for the missing parts. This was one of the most surgical operations of the entire mix process. The two shows sounded very different and Beginnings was played at almost half-speed during the Kennedy Center show; an issue that Jimmy (Pankow) addresses in the documentary film. I had to tempo match the two performances by using iZotope RX to Time Compress each of the 16 tracks until I found the perfect tempo match. It was pretty extreme and, most times, compression software creates really nasty artifacts when it’s pushed that hard. But RX was clean as a whistle, thankfully. Each track was also slightly pitch shifted to match Isle of Wight, even the drum tracks, so the leakage would remain in tune. Then began the task of matching each instrument’s sound between the two shows, though they were recorded with entirely different microphones, preamps, a different tape format (16 track vs 8 track), different guitars, different keyboards, and entirely different environments (outdoor rock festival vs indoor concert hall). I actually had to dumb down the Kennedy Center tracks and make them sound worse than they actually are to get them to match sonically. The grafts turned out to be very seamless and saved both Beginnings and Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?. Now both songs appear as complete recordings in the VI Decades Live compilation, though parts of them were never actually recorded at all at Isle of Wight. I view my role in all of this as that of a museum curator, preparing 10,000 year old broken Sumerian Cuneiform tablets for display. No one wants to pay good money to hear a partially recorded Chicago song. It was most fortunate that we had a very similar vintage recording of the band to save the day.

Stephanie: As you’ve explained to me previously, an important process in taking raw audio tracks from analog tape to be mixed digitally is the process of analog to digital conversion. How did you accomplish this conversion?

Tim: Typically, tape transfer facilities use standard digital audio interfaces to capture audio from analog tape. For instance, a stock Avid Pro Tools interface is commonly used, often synced to a high-end external digital clock. As I said earlier, I felt that we would have only one chance to get this right. For the Isle of Wight recording, I wanted to ensure we were getting a digital transfer that maintained all of the warmth and character of the original tapes. To ensure this result, I literally drove Chicago’s Pro Tools HD rig, along with our Burl Audio B-80 Mothership interface, from Sedona to Penguin Studios in Los Angeles to achieve the highest quality transfer possible. The Mothership would enable the digital files to sound indistinguishable from the original analog tapes. The interface is unique because it has a very robust over-built analog signal path, much like the Studer A827 tape recorder used for playback, with transformers on every input. Compared to most any other digital interface, the sonic difference is night and day. We mix through the B-80 interface in the studio, along with our Chandler replica of the EMI TG12345 console from Abbey Road, circa 1969, the same mix bus that brought us Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon. This robust hybrid of world class vintage analog circuit design and the most powerful digital tools available were a perfect compliment for the tracks of Isle of Wight.

Stephanie: Moving into the deeper trenches of the mix, what were some of the other technical challenges you encountered with the recording and what unusual techniques were required to resolve them?

Tim: The first step in restoring any vintage recording is clean up, which was forensic in this case. Many of the tracks had 50 Hz hum embedded in the audio. This is usually easy to remove. However, the Isle of Wight stage, running 240 volts, had some severe ground loops that created particularly nasty buzzes, with up to 12 audible harmonic overtones. Each overtone had to be precisely identified and individually removed using a combination of iZotope’s RX software and Universal Audio’s Massenburg 48 bit parametric equalizer. The later is quite the fine surgical tool, and helped to identify each of the offending buzz harmonics for removal. The goal was to take out all of the buzz components without changing the tonality or character of the musical instruments, or introducing any strange artifacts into the recording. Earlier in the show, there were also problems with microphone feedback on stage, especially on Mother during James Pankow’s trombone solo. RX removed it entirely. I spent a full week just tracking down and deleting buzz harmonics, trial and error, listening for the effects on the instruments and later, removing tape hiss from all of the tracks. Each track was rendered perfectly pristine, throughout the entire show. I also discovered many clicks and pops that showed up as audio spikes across all eight tracks throughout the show. Using a Wacom Graphic Tablet and Pen, I would manually draw out each spike in the waveform on every track. Those ancient high school drafting classes really paid off here.

Stephanie: Specifically, did you use the spectral repair functions of iZotope’s RX software for removing extraneous noise leaking into the microphones? I imagine this technique is time-consuming.

Tim: Primarily, I used RX to remove very narrow and specific frequencies related to hum, buzz and all of its harmonic overtones, on-stage feedback, as well as tape hiss. It can be a very tricky business to remove a narrow frequency band without appreciably altering the character of the instrument. The spectral analysis shows you precisely where the band has been stripped out of a waveform, and just how narrow it actually is, but ultimately you have to use your ears, not your eyes. Removing extraneous leakage from on-stage microphones is much more of a broad stroke operation. It’s important to use the right tool for the job, and spectral editing to remove stage leakage would just not be practical. A more useful purpose would be something like removing an unwanted resonant ring from a snare drum track, or tightening up the echoey room ambiance from a hotel room interview.

Stephanie: All of the bootleg recordings of this show are very muddy and washed out. How did you manage to tighten up and isolate all of the instruments so well?

Tim: “Manage” is the operative word. I literally managed or deleted all of the microphone leakage on stage that was possible to remove or attenuate. For instance, all of the brass were recorded to only one of the eight tracks. When the horns are playing, the stage leakage is naturally masked by their close proximity to the mics. But during rests, or between notes, the leakage is very apparent and washes out the mix. I manually edited out all of the leakage, much like a noise gate with adjustable fades. When the brass are not playing, their track is silent. I did the same with the vocal mics, Robert’s keyboards, etc. Whenever instruments are not playing, their channel is muted.

Each track became a patchwork of play regions on the Pro Tools timeline. This type of editing is very extreme, and is generally not done on live recordings, but Isle of Wight required extreme solutions. The technique worked only because Danny’s drum overhead mics had mega leakage from everyone else on stage and this leakage provided masking for all of the other channel edits. The end result is a lot more isolation and detail on each instrument and vocal. This process also removed most of the natural stage ambiance, so I used a combination of sculpted digital reverbs and delays to recreate the natural sound of the stage ambiance and better control its balance against the instruments. Truly, my secret weapon is a fortune that I kept from a cookie acquired at some Chinese restaurant in the distant past. It reads “Genius is the ability to take infinite pains.” I really should frame that.

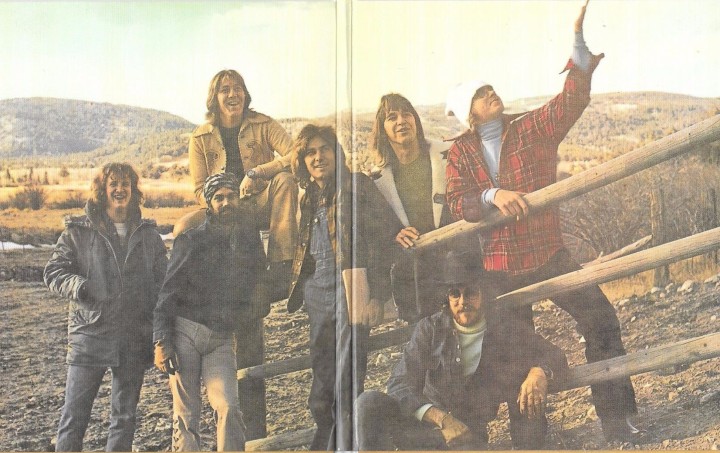

Stephanie: Ray Foulk, the original promoter of the Isle of Wight festival, claims that film footage of the entire festival exits, which is an interesting development. Yet, with only the photos released by Rhino and on fan sites devoted to the Isle of Wight festivals, we can see that the stage plot for Chicago varies from where the instruments are panned for your mix. In particular, it sounds like Jimmy is walking to the center of the stage for his solos, which is a great effect. Did you create a soundstage in your imagination, essentially melding the vintage configuration with the contemporary stage set up, and then mix accordingly?

Tim: My original mix of Isle of Wight (version 1) was actually much like I would mix the current band. I had stereoized the brass left and right, as well as Robert’s keys, with a stereo Leslie effect on his B3, and Terry Kath’s guitar was front and center. It was fun to listen to a modernized version of Isle of Wight, but it did not fit with the concept for the VI Decades Live box set. So it was decided to go with a vintage panning configuration that had been used on previous live Chicago recordings. The instrument’s pan positions were also chosen for how they establish the fundamental balance of the mix. Terry’s guitar is very beefy and produces a lot of low frequency energy, so he can hold up the entire left side of the mix. We needed a similar energy to balance that out on the right, so Robert’s keyboards balance Terry’s guitar on the right side. The kick drum, snare and Peter’s bass fill the middle, with the drum overheads spreading out the stereo field.

These elements create the general balance or scaffolding for the mix, distributing the energy relatively evenly. From there, the brass, solos and the vocals can sit anywhere on top of that foundation. I tried to strike a balance between the brass section sitting mid-right, yet not feeling too static, as if they never move. So, it made sense to have some of the solos take center stage on occasion. It makes the mix sound more alive and dynamic.

Stephanie: How would the soundstage we are hearing on your mix have differed from what the actual audience at Isle of Wight heard in person?

Tim: Ironically, the actual live mix at the Isle of Wight festival was very likely mono! Most live mixes were mono in 1970. On looking at photos of the band’s stage setup, if the mix were literally panned in stereo where the guys were standing on stage, the whole mix would feel whacked out of balance. The brass would be far left, with Robert Lamm just next to them, Terry Kath in the center, and the drums and bass would be way over on the right side. What is historically accurate does not necessarily translate into a well balanced mix.

Stephanie: I know you have a very deep knowledge of and experience in analog recording techniques and equipment. Your Sedona studio is equipped with many plug-ins that emulate those classic sounds. What technology did you employ on Isle of Wight?

Tim: I used both analog-modeled plug-ins and actual outboard analog processors. On the plug-in side of the equation, I have always strived to use tools that model the harmonic saturation, character and behavior of the classic processors heard on most hit records made over the past 50 years: Universal Audio’s emulations of the Neve 1073 EQ and preamp, SSL E channel, Urei 1176 compressors, Teletronix LA-2A, Pultec EQ, Oxford De-Esser, Neve 33609 stereo bus compressor, Slate Digital Virtual Console Collection, and the Slate Virtual Tape Machine. These kinds of plug-ins used to be essential to give digital audio a more familiar, warmer, analog sound.

However, due to our studio upgrades such as the Burl Audio Mothership interface, the Chandler summing mixers, combined with the actual analog tape source of Chicago’s Isle of Wight recording, the digital recording already sounded completely analog, and digital emulations would often provide too much “color” or harmonic saturation. So it was necessary to simplify the mix in terms of plug-in use, choosing more transparent processors like the Massenburg EQ or the Eiosis Air EQ, keeping it more organic.

Stephanie: Danny Seraphine’s drums sound amazing, and we hear details of his performance that are lost on other live recordings of this era. What is going on there?

Tim: If you’ve seen photos of the band on-stage during the Isle of Wight festival, you can see that there are only three microphones on Danny’s drum set: two overhead mics placed in a rather wonky “XY” pattern and a bass drum mic on a boom stand, raised up above the drum and placed roughly two feet in front of it. This is about the worst possible way to record a drum set live on stage. Therefore, Danny’s drums required more attention than anything else in the mix. I copied all of his tracks and gave the drums ten Pro Tools tracks. Three stereo pairs of overhead mics involved various degrees of parallel compression, blended with the uncompressed main stereo pair. One pair of overhead tracks were intensely “musically limited” by an outboard pair of vintage Inovonics 201 limiter-compressors. This device was a secret weapon of a handful of top engineers in LA during the 70’s and 80’s, such as Bruce Swedien who recorded Michael Jackson and one of my most esteemed mentors, Barney Perkins, the top Motown mixer of the day. Barney would not do a mix session without a pair of Inovonics 201s on hand, as they were an essential part of his unique fat sound.

Stephanie: Wow! You have some analog rack gear from the “old days” in Sedona that have become rare these days.

Tim: They’re not easy to find. We probably have the only three Inovonics in Arizona. I wish one of the plug-in manufacturers would build a software version, but it’s just not on their radar yet. It really was a well kept secret. The Inovonics 201 was originally invented as an early VCA style radio broadcast limiter, to keep live program content loud and even, like the later Orban Optimod limiter. But the 201 has a wonderful effect on drums and bass, making them fat and even, with a uniquely extended slap attack. The combination of four pairs of stereo overhead drum tracks, with the Inovonics as part of the blend, made the snare and toms actually sound close mic’d. But the kick drum still needed to be dealt with. This is where I made the first decision to go rogue from the budget and just do what needed to be done, though I would personally have to pay for this next adventure myself.

I spent five days carving up every single kick drum beat with the Wacom pen and graphic tablet, making each kick beat an individual Pro Tools region, isolating the kick beats from all other drum sounds and stage leakage. This enabled me to radically sculpt and compress the kick drum sound like a sample, and then blend it back into the linear, unedited kick drum track. The result had the effect of moving the microphone from two feet away from the drum, to placing it inside of the kick drum. The process increased the overall foundation of the mix 100-fold and brought out amazing detail in Danny’s foot work. At times, it sounds like he is playing a double kick drum set, but he’s doing it all with one foot. It was a painstaking process, an insane amount of detail work, but it was worth every one of the thousands of edits I made to achieve Danny’s forensically enhanced drum sound. After all, this mix is forever.

Stephanie: The recording industry today is increasingly mixing new releases to be optimized for streaming and download services such as Spotify and iTunes, which on the one hand increased the audience for this boxed set but might be unfortunate for some audiophiles who appreciate fidelity. With a set of Barefoot MM27s in your studio, how does this dual market reality affect your mixing?

Tim: It doesn’t. I mix to achieve the highest quality and greatest detail possible from the source material, equipment and software I have on hand. I was inspired by the work of the great engineers who came before me; such as Roger Nichols (Steely Dan), Phil Ramone (Chicago, Billy Joel), Chet Himes (Christopher Cross), Joe Chiccarelli (Frank Zappa, Elton John, U2, the White Stripes), Humberto Gatica (Chicago, Michael Jackson), Barney Perkins (DeBarge, Steely Dan, Dr. Strut) and Bruce Swedien (Quincy Jones, James Ingram, Michael Jackson). The list goes on. These men set precedents for the highest achievements in sound recording long before Pro Tools and audio streaming ever existed. Their achievements have yet to be surpassed in this digital age. I am honored to have worked alongside many of them in my days as a staff engineer.

Whenever I do a mix for Chicago, I am cognizant that I am standing in the shoes of Phil Ramone, and other great engineers. It falls to me to live up to their legacy and at least maintain the bar of excellence that they’ve set, while striving to raise it. Spotify and iTunes do not enter my consciousness at all, as I am mixing for a pure, jitter-free, uncompressed, high resolution digital file, or for vinyl. The streaming and download services do all they can to maintain that quality, but Bruce Swedien did not mix Michael Jackson to optimize for audio cassette. One of the requirements for that little “Mastered for iTunes” label, is that the compressed audio file must be derived from a 192 kHz, 24 Bit master.

Mixes are fickle things. Ideally, you want them to translate perfectly no matter how they are played. But if you mix for the highest possible listening scenario, streaming and compression techniques will yield the best sound they are capable of. Archival recordings like Chicago at Isle of Wight bring with them a unique set of challenges. Due to the radical limitations of the source material, the mixes sounded very different on different kinds of speakers. A modern, well recorded rock project will translate beautifully when mixed on the Barefoot MM27s. But as expensive and revered as these monitors are, they were not the right speakers to mix IOW on. It was a trial and error process of listening on up to eight different pairs of monitors, and getting feedback from band members, from the label folks, and from DNA Mastering, until I finally arrived at a mix that translated well on most anything. Sometimes it’s not always a straight path to that goal, but I think Isle of Wight will make a lot of people happy, whether they are streaming or listening to the CDs on a vintage McIntosh home stereo system.

Stephanie: From the photographs of the band onstage, we can see that Terry Kath was playing his Les Paul Professional, an unique guitar in the annals of Gibson history, through a Vox cabinet. Was one track dedicated to his guitar alone? How did you treat his guitar to sound so upfront as we are hearing on Isle of Wight?

Tim: Fortunately, yes, Terry Kath’s guitar was assigned to its own track. The Vox was a prominently mid-range forward speaker cabinet. On its own, it did not produce the beefy tone that Terry later became known for, nor did the Les Paul Professional have the bite of Terry’s later guitars, such as his infamous Pignose Telecaster. Given the importance of this recording to posterity and for the pure blissful enjoyment of Terry’s fans, an important decision needed to be made. It was a Giles Martin moment. What I mean is that there were moments when Giles was re-mixing the Beatles Sgt. Pepper’s album, that certain decisions had to be fretted over as to whether they would be considered sacrilegious, like panning the Beatles vocals to the center of the mix. I felt compelled to make Terry Kath’s guitar track sound a bit larger than life. In this mix, his guitar track has been re-amped through three separate guitar amplifiers, which are then blended back into his original Vox guitar track perfectly in phase. Amp number one is a vintage Music Man that came straight out of Chicago’s warehouse in LA, an amp that Terry likely played through at one time. Amp two is a vintage 1964 Ampeg flip-top B-15 bass amp, which provides a thick bottom end to his tone. Amp number three is Lee’s modern Egnator that normally lives in the studio. Guitarist Keith Howland has long used Egnators on stage with Chicago.

Stephanie: By “blended” did you initially make three additional Pro Tools tracks, one for each amp, and then bounce them into the original guitar track or did you keep the four guitar tracks separate?

Tim: Terry’s re-amped guitar parts are each on separate Pro Tools tracks, with their own individual processing. Once I arrived at the tonal balance that worked well, I grouped all four guitar tracks to lock in their balance and automate their levels as one guitar track. I don’t like to bounce tracks if I can avoid it. The four guitar tracks are then routed to a stereo pair of analog inputs on our Chandler summing mixers and panned to appear wider, filling out the left side of the mix, rather than emanating from a single point. The six guitar input transformers on both the Mothership interface, and the Chandler summing mixers also add a weighty, beefy character to Terry’s overall guitar sound, giving it more of an intimate studio character. It was a no compromise way to honor and memorialize Terry’s performance at the Isle of Wight festival.

Stephanie: What inspired using a mix of different amps for Terry’s guitar sound? Is there a precedent for this technique or your own innovation?

Tim: Stevie Ray Vaughan was known to record his guitar through up to 12 different amplifiers simultaneously in the studio, so Terry is in good company having his guitar sound layered through four amplifiers here. It really felt like a holy moment to hear Terry rocking loud and proud out of an actual guitar amp again! I had chills. The additional amplifiers were not used to add more overdrive or change Terry’s tone significantly, but only to beef up his recorded sound and add more presence to it. It’s akin to walking out into the studio and adjusting the guitar tone on his amplifier or moving a microphone, rather than reaching for an equalizer on the console. Engineering icon Al Schmitt has long preferred to move or change a microphone on an instrument, rather than use EQ at all. Re-amping Terry’s guitar was a similar organic process. It was like having him back in the studio for a few short hours and it gave me a much bigger guitar sound to work with. In addition, three separate 48-Bit Massenburg EQ plug-ins were used, each one corresponding to one of Terry’s three pick-up switch positions on his guitar. Whenever he switches his pick-ups during the show, a different EQ is engaged which is optimized to that particular switch configuration. All of his pick-up switching is automated in the mix.

Stephanie: Chicago is captured in this moment in time, in front of an audience of many hundreds of thousands, as a young and hungry band. On your mix, each vocalist has retained their character and urgency, despite the use of some substandard microphones that were common in 1970. How did you treat the vocal tracks for an authentic and emotive experience for today’s listeners?

Tim: All of the vocals were originally recorded to only two of the 8 tracks. I separated each vocalist and gave them two individual vocal tracks each, with their own unique signal processing and EQ. The harmony background vocals were also moved to a separate track and stereoized to emanate from both sides of the mix, surrounding the lead vocals in the center. This really helped to open up the vocals and give them much better definition and presence overall. I also used a lot of subtractive EQ on each vocal to remove unwanted or harsh frequencies inherent from the dynamic microphones. This tends to make funky inexpensive microphones sound a lot more expensive! A similar process was used on Robert Lamm’s keyboards, which were also combined onto a single track. All of his Hohner electric piano sounds and his Hammond B3 organ were each separated out onto their own individual tracks for tonal optimization. In all, the original 8 tracks of the Isle of Wight recording became almost 50 tracks in the final mix.

Stephanie: While this show capture an era when Terry Kath was very much the band leader, what are the unique challenges of mixing a seven-piece band where you have a combination of amplified electric instruments with acoustic brass and woodwinds, particularly in terms of the volume levels? I recall during the film, Now More Than Ever, that David Foster has to mediate some conflicts between band members by trying to keep their hands off the faders!

Tim: Truthfully, because everything is close-mic’d, it’s a pretty level playing field to work with. It matters not that some instruments are electric and some are acoustic. I do prefer to isolate the instruments from one another as much as possible, which allows better control over their harmonics and tone. So technically, volume levels are not really an issue; it is purely an artistic choice. In the old days, the band members did spend a lot of time in the studio. Prior to the existence of mix automation, it was necessary to have many hands on the console riding faders. The mix was a performance by the band and this would lead to the kinds of volume battles that David Foster alluded to in the film. Everyone would have their own preferences for balance.

These days, mix automation is fully in control, and the band is far too busy performing to ever attend a mix session. On occasion, Lee will sit with me when he is home, but primarily I work on my own. I can literally draw minute mix level changes with a graphic tablet that are humanly impossible to reproduce with a hand on a fader. Our reflexes just aren’t that fast. But over the years certain mix conventions have become standards for the band. For instance, when I mix the brass, you will always hear trombone on the left, sax/flute in the center, and trumpet on the right. Overall, major brass parts (hooks) and solos are about equal in volume to the vocals. It is part of what makes up the “Chicago Sound.” As part of this convention, the brass are typically always doubled, except for solos. They have been doing this since the days of CTA and the chorusing effect of doubling each of the horns has long been a part of the band’s signature sound.

Stephanie: Do you have a favorite personal favorite track from Isle of Wight? I appreciated Mother very much because it was a time when audiences were open to hearing songs they didn’t know yet but soon would. Plus, the band was really tight on the harmonized section, and it shows their dedication to the carefully crafted songs in a time when free-form jamming was becoming more popular.

Tim: It’s a tough choice, as there are so many wonderful moments on both discs. I do appreciate your viewpoint on Mother, and the fact that audiences back then were more open to the adventure of new music, new ideas, and in fact, awaited with baited breath for the next new album to be released. Artists did not feel so pressured by their success to just play the hits back then, and recording or performing were still purely about the art of music. not about the money, for the Baby Boomer generation. I think that Chicago’s recent decision to feature the songs of Chicago II on their tour this year is an inspired attempt to move back towards those values, being driven by the art of music and not just playing it safe with the hits. One of my personal favorites in the Isle of Wight collection is It Better End Soon on disc two, track one. It captures the band in full jam mode with Terry Kath ecstatically on fire. It is among the most passionate and high energy moments the band has ever recorded. If you could make love to music, It Better End Soon would leave you a sweaty, saturated mess when it was all over.

Stephanie: In terms of attendance, Isle of Wight in 1970 was estimated to be a bigger festival than Woodstock. In addition to the sheer size of the band’s audience at the time, what do you feel made the Isle of Wight mix a milestone for Chicago and how did you approach your mix accordingly?

Tim: When Robert Lamm first learned that Rhino Records were going to resurrect this recording, he said that he always thought Isle of Wight was “a sow’s ear that could never be turned into a silk purse.” Until recently, the technology needed to resolve many of the recording’s technical issues did not exist. But three months later, Robert was calling this an “enhanced mix.” As an original member of the band, lead singer, and a primary writer, Robert is not easily impressed. He’s seen it all. I felt it was going to be a near impossible feat to elevate the Isle of Wight recording into a master that Robert could feel good about. I have never been more pleased that Isle of Wight reached this high water mark.

One of the final stages that put it over the top was a two-tiered mix process I worked out specifically for this recording. Many top engineers use their own unique parallel compression methods on their final mixes to make them sound as big and as loud as possible. After considering what might work well as the icing on the cake, I developed an idea that seemed well suited to preserve the dynamics of the mix, while increasing overall presence. I made individual stems of each main part of the mix: Terry’s guitar, the vocals, the brass, Robert’s keys, Peter’s bass, and Danny’s drums. Next, I imported the final 96 KHz stereo mix into a new Pro Tools session, along with each of the stems. Each stem was then individually compressed and blended very slightly into the final mix, with their respective levels automated throughout the show. Rather than using parallel compression across the entire stereo mix bus, I adjusted the compressed stems individually according to their dynamic relationship to the full mix at any given point in time. Very subtle use of the stems went a long, long way in creating more presence, without diminishing the dynamics of the mix. Perhaps only 5% to 10% at any point in the mix were used. Ultimately, this is why Terry’s guitar and the vocals sound so present and the drums are also so solid, though they were recorded with only three microphones. The Isle of Wight mix represents a number of milestones and innovative ways to resolve vintage audio limitations. But mostly, it’s just plain fun to listen to, and that’s really what it’s all about.

Stephanie: Also on VI Decades Live is your mix of Goodbye from a different show, Chicago at the Kennedy Center (1971). It’s acoustically perfect and perhaps the best sounding vintage Chicago live track that I’ve ever heard. How does your mix of this track differ from Isle of Wight?

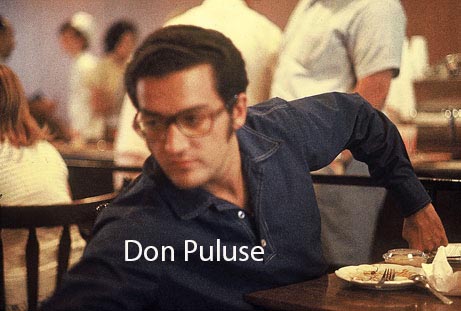

Tim: This is probably my favorite mix in the entire box set. It was simply well recorded by Don Puluse, the original engineer for the Chicago II album and staff engineer for Columbia Records. Goodbye was recorded to 16 track 2” tape at 15 ips (inches per second), using excellent microphones, a quiet signal flow, and it all made my job so much easier. The entire mix and restoration for Goodbye was completed in just two days. Isle of Wight required nearly three months to mix, with an unbelievable amount of processing, editing and automation. Because of its superior recording quality, Goodbye (from Chicago’s 1971 Kennedy Center performance) required very little processing, and it just sounds gorgeous and organic. I did use iZotope’s RX software to remove the minimal tape hiss that existed on each of the 16 tracks. This step alone made it sound like a modern HD recording. Goodbye is perhaps the finest archival live Chicago mix to date, and required the least amount of studio processing of any previous live show I have ever mixed for the band. I have to give all of the kudos to Don Puluse for doing such an impeccable job recording the Kennedy Center performance.

Stephanie: What’s next for Tim Jessup and Chicago Studios in Sedona? Are there any projects you’re currently working on, or would like to mix, that we can look forward to in the future?

Tim: Well, there has been some discussion about possibly remixing Chicago Transit Authority this year. We’ll have to wait and see if that happens. I’m currently working on several film soundtracks, including composing the score for one of them. However, mixing Chicago’s Isle of Wight performance enabled me to develop some very effective techniques to deal with the issues inherent in all of the Isle of Wight recordings captured by Pye Studios in 1970. It would be enjoyable to transform the recordings of some of the other artists who performed during this festival, for instance a re-mix of Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Miles Davis, The Who, The Moody Blues, Jethro Tull, and so many others. There were many iconic performances during this festival that can be elevated into mixes with far greater detail and clarity.

Lastly, Chicago is always writing new material, though their touring schedule rarely allows for recording it. There may actually be a window later this year when we can begin to record and release new material. Rather than tracking on the road, we would be recording much of it here in the Sedona studio this year. It remains to be seen how it will work out with their touring schedule, but the band does have a strong intention to record new material. Let’s keep our fingers crossed.

Chicago’s set at the Isle of Wight festival in 1970 was symbolic of their forward momentum from playing dank and conservative Midwestern clubs only three years prior to playing in front of an international audience of hundreds of thousands on August 28, 1970 at Afton Down on the Isle of Wight. Flying to England on their second trip outside North America just for the momentous occasion, Chicago at Isle of Wight captures the band at the height of their musical experiment as a band unafraid of fusing genres and expressing their unbridled energy on a grand scale. Naturally, the comprehensive and meticulous engineering of Tim Jessup was the only choice for Chicago and Rhino Records to memorialize this iconic set. Tim’s work shows the professional audio community what is now possible when mixing archival tapes in a hybrid environment that employs innovative digital techniques while preserving the warmth of analog sound.

Chicago’s set at the Isle of Wight festival in 1970 was symbolic of their forward momentum from playing dank and conservative Midwestern clubs only three years prior to playing in front of an international audience of hundreds of thousands on August 28, 1970 at Afton Down on the Isle of Wight. Flying to England on their second trip outside North America just for the momentous occasion, Chicago at Isle of Wight captures the band at the height of their musical experiment as a band unafraid of fusing genres and expressing their unbridled energy on a grand scale. Naturally, the comprehensive and meticulous engineering of Tim Jessup was the only choice for Chicago and Rhino Records to memorialize this iconic set. Tim’s work shows the professional audio community what is now possible when mixing archival tapes in a hybrid environment that employs innovative digital techniques while preserving the warmth of analog sound.

Tim Jessup and Chicago Sound Studios can be reached through his website at http://timjessup.com and on Facebook. Stephanie Carta writes about films, music, and literature. She learned record production, and analog engineering and mixing at the Media Arts Center in Hartford, Connecticut. She can be reached at stephanie.carta33@gmail.com.

Tim Jessup and Chicago Sound Studios can be reached through his website at http://timjessup.com and on Facebook. Stephanie Carta writes about films, music, and literature. She learned record production, and analog engineering and mixing at the Media Arts Center in Hartford, Connecticut. She can be reached at stephanie.carta33@gmail.com.