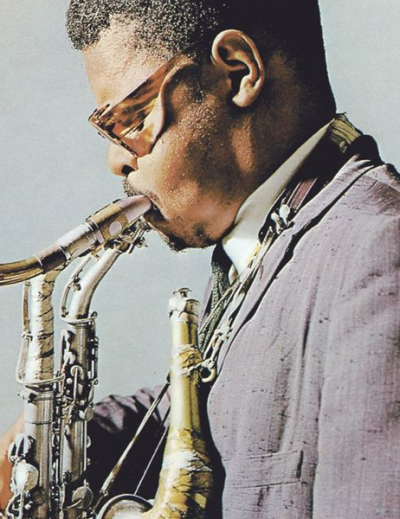

In our current era of hyper visuals and social media, would Rahsaan Roland Kirk, striking in his onstage persona with multiple woodwinds and assorted whistles hanging around his neck, have been more accepted than he was during his lifetime in the middle of the twentieth century? Maybe. Kirk was not the first to play multiple woodwinds simultaneously, but it is his life and music that has attracted new attention, discovered by a new generation fascinated and influenced by his unorthodox style. Recently released on DVD and Blu-ray, Rahsaan Roland Kirk: The Case of The Three Sided Dream, a documentary film by Adam Kahan, provides a very entertaining and invaluable look at a small slice of his life and career.

Kahan’s film is made up of interviews with Kirk’s family, friends, and bandmates; a small selection of televised performances; and original animated segments. Interspersed between the live action, the colorful and lively animations are charming, embracing a visual style somewhere between School House Rock and Yellow Submarine. This is a mostly uplifting film. Refreshingly, its production style does not pander to the hyperactive or inattentive. Although Kirk’s life was cut short by natural causes, there is no overarching tragedy to portray (unlike the subjects of other documentaries that will be reviewed here in the future), leaving Kahan free to indulge in a whimsical style appropriate to his charismatic subject.

Much of the discussion around Kirk’s legacy in jazz, or as he would call the genre, Black Classical Music, concerns whether or not one must downplay the visual spectacle of Kirk to appreciate his musical contributions. The documentary argues correctly that it was not a zero sum game between the visual and the sonic elements. Kirk sought attention not as a gimmick, as some critics claimed, a term Kirk reviled, but rather because of his child-like embrace of showmanship. The footage from his performances exude his infectious spirit.

He was an artist who sincerely embraced the idea that music was a way to move people emotionally. As a young boy Kirk turned a garden hose into a trumpet, reminding me of a six year old student banging a stick against a light post while proclaiming that you can make music with anything. Perfecting the circular breathing technique, Kirk embraced the musical equivalent of a stream-of-consciousness literary point of view. Not needing to pause for a breath, he was free to blow with uninterrupted improvisational invention. Along with Kirk’s emotional impulse was his innovation on woodwinds either together or singularly. Playing multiple instruments at the same time allowed him to explore new frontiers harmonically and melodically. He was a reed section “all together in one mouth,” also credited with creating “a brand new linear category on the saxophone.” I was particularly thrilled with the clips of him playing old school jazz on the clarinet.

Kirk’s life off-stage, shown in glimpses from home movies, portray a devoted family man, well-adjusted despite being blinded as an infant by a nurse’s negligence. Some episodes in his life evoke not just sympathy but one also feels the injustice of the treatment of man with many targets upon him: creative, disabled, proudly Black. He suffered a stroke at age thirty-nine and was left partially paralyzed. Yet, he made a comeback, using instruments modified so he could play them one-handed, before passing away in 1977 at the young age of forty-two. Most of all, the main impulse for his life was not bitterness but an intrinsic love of sounds and expression in music. Kirk was attuned to sounds both ecological and anthropomorphic, a classic example of how being deprived of one sense heightens another.

Prior to recording under his own name, Kirk played with Charles Mingus. Unfortunately, Kahan skips over the Mingus years, focusing instead on his time recording and gigging under his own name. Fans must scour for other sources to fill in the blanks. His early career was appreciated by writer Barry McRae who astutely chronicled this era in some detail his 1967 text, The Jazz Cataclysm. It is heartening that McRae, a writer contemporary to Kirk, described him as a “brilliant soloist whose playing is full of humanity, humour and the vital reality that distinguishes the finest players.” This humanity is what attracts me to Kirk’s music and the factor that most explains the renewed interest in his life. Kirk was someone who learned the formal rules of music and theory, then felt free enough to disregard them.

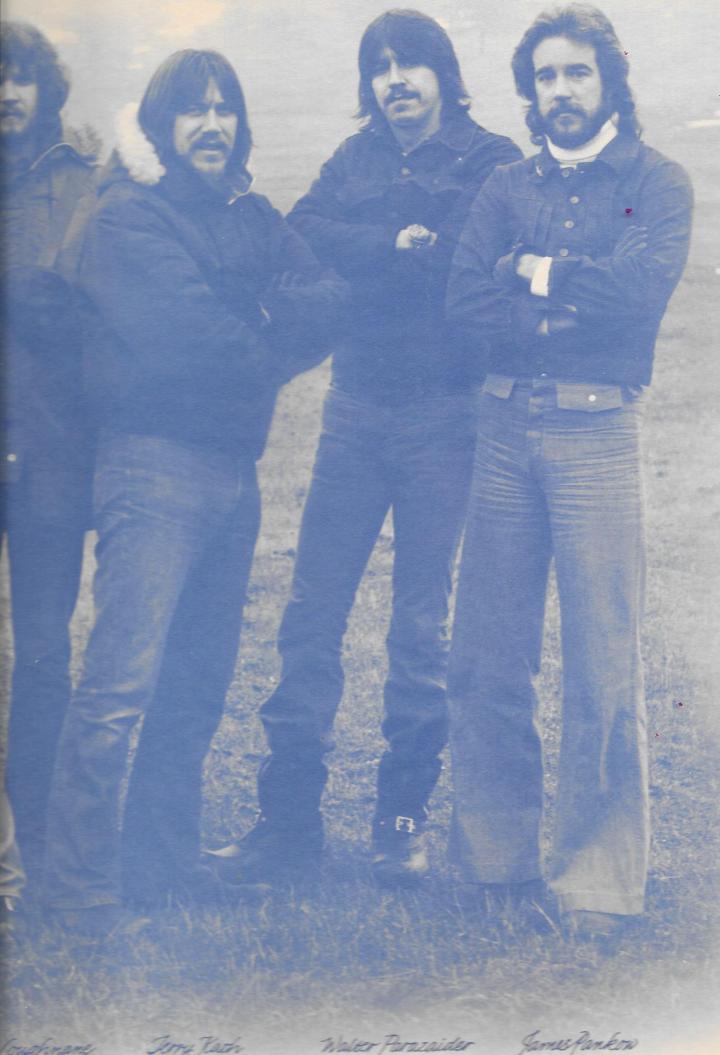

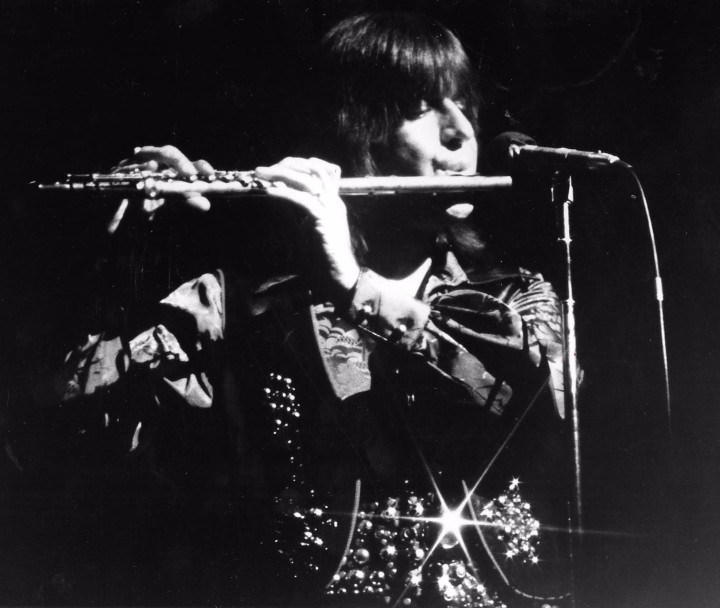

Other contemporaries appreciated Kirk as well. Walter Parazaider of Chicago, trained in classical clarinet before his vision of a rock band with horns came to fruition, has stated that he was a fan of Kirk’s and took a similarly heartfelt approach on saxophone and flute, boldly experimenting with free styles and injecting his own humor and showmanship at the right times too. Younger enthusiasts include guitarists Derek Trucks who recorded his own version of Kirk’s “Volunteered Slavery” and saxophonist Jeff Coffin who can play both alto and tenor simultaneously.

Looking at Rahsaan Roland Kirk’s legacy from a twenty-first century lens, I think Kirk would share in the disappointment that Black music and Black artists are underrepresented in the Americana or American Roots Music genre. The moniker of Black Classical Music had nothing to do with comparing it to European classic traditional. Instead, Kirk believed that Black musical traditions were rooted in the American experience. If the cerebral nature of post-swing jazz created a rift between it and roots music, Kirk did all he could to bring it back to those roots. Before viewing the film, I was unaware of Kirk’s activism and foundation of The Jazz and People’s Movement which took direct action to get more Black music and artists on television. Fast forward a few decades, the Americana scene is strangely made up mostly of white artists.

As someone fully enchanting by Kirk’s music in retrospect, I truly wish for a comprehensive and earnest biography of his life and career. Ultimately, The Case of the Three Sided Dream doesn’t give us that full picture. The film is, however, a heartfelt tribute. The joy Kirk brought to the stage, as well as the tragic misunderstanding of his music and mission, reverberated throughout. It is a communion with the fragile humanity of a blind Black man who was never afraid to speak his mind in music or in words and deeds.

(Rahsaan and his assorted instruments in an undated photo.)