The artistry of Chicago II and its place of honor in Chicago’s canon is unquestionable, regardless of the format. It would be impressive if heard over a transistor radio. Chicago’s second album incorporates rock and roll, jazz, and classical influences into a four-sided journey with these different strains of music absorbed and re-imagined by these seven musicians. Chicago II including the suites: Jimmy Pankow’s Ballet For A Girl In Buchannon and It Better End Soon, a collaboration between Robert Lamm and Terry Kath featuring Walter Parazaider on an extended flute solo. The second side starts off with a 2:34 minute sweet pop song, Robert Lamm’s Wake Up Sunshine, seemingly tailor-made for retrograde AM radio but never released as a single. The orchestration on the Memories of Love suite is reminiscent of The Moody Blues’ album, Days of Future Passed (1967) and on Beatles’ songs such as Eleanor Rigby. Even with disparate styles of music on II, the album flows together with perfect synchronicity. As the liner notes state in a direct message, which I read for the first time thirty years ago as a preteen Chicago fan, and symbol of the earnestness of the album and its song order: “This endeavor should be experienced sequentially.”

Chicago II is a revered album, and I greeted the news of its being remixed by Steve Wilson, whose previous work including remixing Yes, Jethro Tull, King Crimson, with excitement and also some trepidation. There is a substantial difference between a remix and a remaster. For those unfamiliar with recording techniques, think of making any typical rock album as a multi-step process. First, instruments and vocals are recorded on tracks, starting with the rhythm section, and then overdubbing the rest of the instruments and vocals. Chicago II is a 16-track recording, and all recordings from the 1970s and prior were analog recordings. While listening to this record, as well as Chicago Transit Authority, I often think about the challenges posed to the engineers* of Chicago’s earliest albums who had to put a seven-piece rock band onto so few tracks. While this was a manageable task with typical rock band instrumentation, the horns required separate tracks for the arrangements, usually double-tracked, and the solos. The recording engineers at CBS Studios were in charge of this entire process, from setting up the studio, placing the microphones, recording the musicians, and then mixing and mastering the album. Producer James William Guercio was limited in what he could do as only those who were members of the CBS union could use the equipment in their studios per standard practices.

Once the recording is finished, the individual tracks of the song are mixed, adjusting things like frequency, volume, dynamics, and where each particular track will be heard in the stereo spectrum. The next step is mastering for release on a physical format such as a vinyl record or compact disc, with the mastering engineer ensuring that the full album has a cohesive sound. The remastering process that takes places for usual reissues does not touch the individual tracks. A remix, however, goes one step further back in the process. The task of remixing Chicago II by Steve Wilson involved digitally remixing the 16 individual tracks of the album. In essence, Wilson was able to overwrite the work of the CBS engineers and create something that was very different than what we are used to hearing. However, Steve Wilson stayed close to the original mix of the album, producing a clearer and cleaner mix than Rhino’s previous remasters of Chicago II.

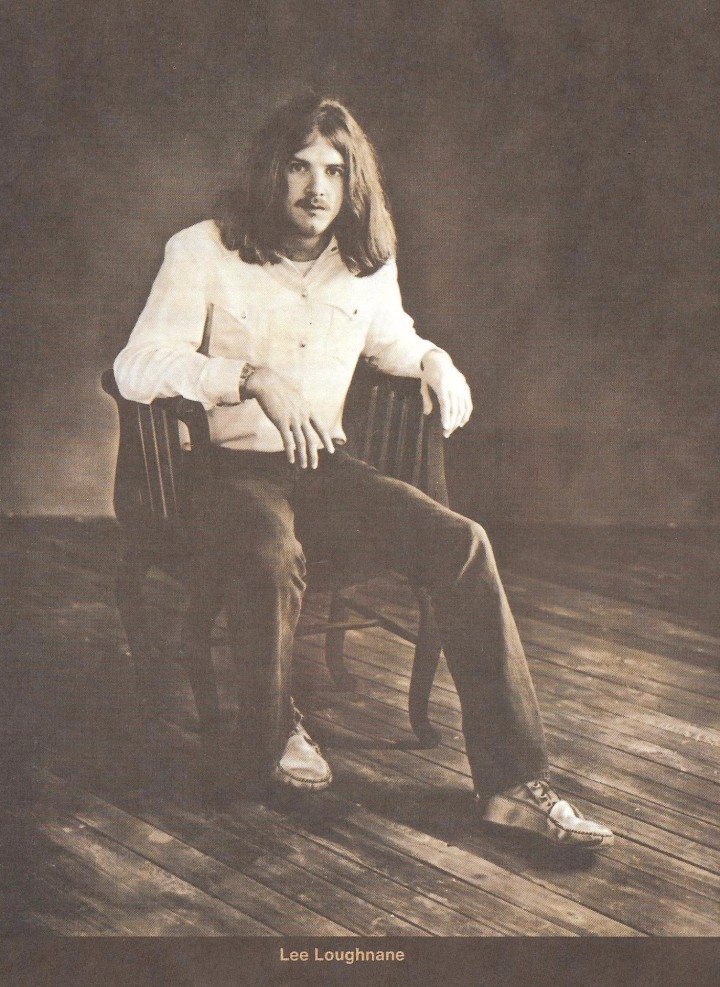

Remixing any classic work by an iconic band is something like playing God. If there is one moment in Chicago II where some divine intervention might be helpful, it is during the horn solos following the soli section on Movin’ In. Walt belts out an alto sax solo, full of passion and dissonance, his shout out to the free jazz movement, beautifully ironic that it was recorded in a studio with so many rules as CBS. Jazz fans might have been reminded of Ornette Coleman or some of John Coltrane’s freer works from the last phase of career. Lee Loughnane on trumpet and Jimmy Pankow on trombone then take the solo section back down to earth, all together forming a symbolic and attention-grabbing moment on the first song of the record. In the original mix and the remix, this part of the song has some odd dynamics, the comping louder than the solos, and it would have been more powerful to hear the solos louder and much more present in the mix. In comparison, on Ballet the original dynamics are something close to heavenly perfection.

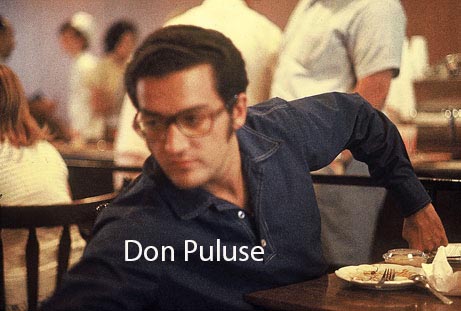

Chicago’s history recording at CBS Studios in New York City from 1969 to 1972 is, sadly, not well documented. They worked in studios where if the walls could talk, they would tell large chapters of American musical history. Usually, Chicago recorded at Studio B at 49 East 52nd Street, home to recording engineer Don Puluse. Occasionally, brass was recorded at the studio known as “The Church” at 30th Street, a studio that was particularly suited to big orchestral groups and big bands who were recorded playing live as a group, originally onto three or four tracks with little or no overdubbing. Engineers of Chicago II include Don Puluse, Brian Ross-Myring, and Chris Hinshaw (who famously conspired with The Byrds to break the studio rules). The remastering engineer of Chicago II, Robert Honablue, was the first African-American engineer at CBS Studios.

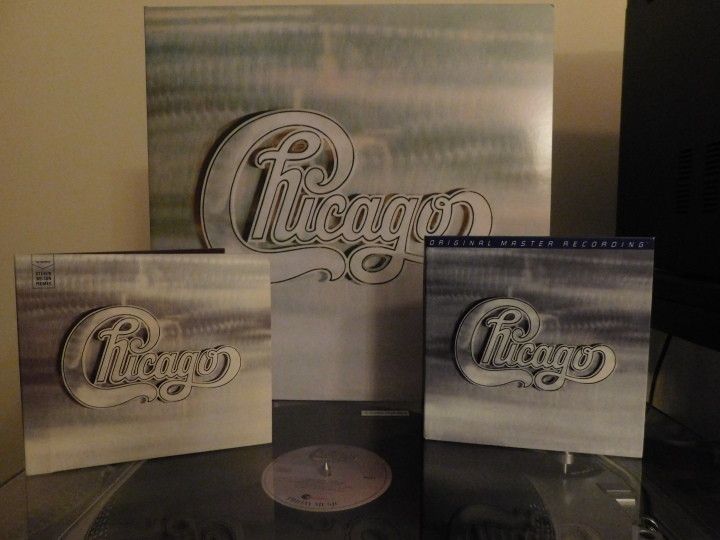

The work of the CBS engineers was truly commendable considering the milieu in which they operated, and no remaster would sound good if the source (the master tape) was faulty or deteriorated. The best reissue of Chicago II shows the beauty of their work as it was done in 1969, released on dual-layer super audio compact disc (SACD) by Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab. However, MoFi reissues are limited editions, and it is now out-of-print. MoFi remasters their releases using the original master tapes that, in their words, “exponentially expands the soundstaging dimensions, imaging proportions, and dynamic information, allowing the songs to breathe and enjoy a roominess that enhances the stellar performances and interwoven structures.” The tape hiss of the original master is actually noticeable louder on the SACD, making the experience feel and sound closer to the source recording, as if one were listening to the master tapes in a studio. Even though it is a digital format, this SACD retains the warmth of analog, especially noticeable on the naturally resonant baritone voices of Robert Lamm and Terry Kath which have a presence on this remaster that is especially appreciated on Poem For the People and Colour My World.

The original sound quality of Chicago II was limited by many factors, the physical characteristics of the studio facility and the limitation of the recording equipment available to them at the time. With today’s technology, audio engineers have limitless options. MoFi’s reissue preserves the analog warmth, while the Steve Wilson remix embraces the advances in digital mixing and emulation. Wilson has taken heed to respect the integrity of work done by those brave and talented men at CBS records. The MoFi SACD revealed the beauty of the recording techniques and studios, a vintage sound that is still appreciated and emulated with new electronic technology. If Chicago were to remix their own works using the best available technology of today, I can only imagine just how beautiful the result would be.

On the other side of the audio spectrum, for Chicago fans who would rather listen to their “old records,” the Friday Music reissue of II is the best way to listen to Chicago II on vinyl, preserving the sound quality and familiar experience of playing a record. Friday Music uses 180 gram weigh records, a slightly heavier record than the first original pressing of Chicago II by Columbia Records. This reissue was remastered by Lee Loughnane and the founder of Friday Music, Joe Reagoso, using the Chicago Records master tapes.

While vinyl lacks the enhanced frequency range and extremes of stereo separation of the digital formats, many Chicago fans will appreciate the analog warmth and replication of the original listening experience as you remember it, perfect for introducing your children or grandchildren to vinyl records. These pristine new records are free from skips and pops and come in a replica of the gatefold record cover, with each record housed in an anti-static sleeves. This whole package is a faithfully reproduced by Friday Music, lacking only the poster, but reminding me of my initial discovery of a vintage copy of Chicago II in the family basement but without the deterioration caused by years of improper handling and storage (which happened before I claimed it).

The re-release of The Beatles catalog in 2009 on two boxed sets, stereos mixes for modern tastes and mono mixes for purists, showed how the newest technology and processes could make recordings from the 1960s sound even better. While Rhino’s Chicago Quadio box on Blu-ray appealed to the audiophile market, new reissues on compact disc would appeal to a larger audience. The new transfers from the master tapes of The Beatles catalog for the ‘09 reissues were a large factor in the improved sound quality and expanded frequency range, greatly improving upon the first remasters when The Beatles were first put on compact disc in the late 1980s. Chicago’s catalog deserves the same respect as The Beatles has been given. Whether new remasters of the classic era of Chicago were packaged together in a box set or sold one-by-one, it would be worth my money to repurchase Chicago’s first eleven albums again.

* Tim Jessup, Chicago’s current sound engineer, and Jim Reeves, recording engineer at CBS from 1969-1972, have kindly shared their insights with me. The work of audio engineers tends to go unrecognized, but it truly makes a difference.